Regency Detective stories

Over the last few years, I have posted several pieces about detective stories set in the past. This is a very rich field and each year more and more excellent ones are being written. This little essay is the first of two about murder and mayhem in the Regency period in Britain. For those of us brought up reading the immortal works of Jane Austen, this is one of those magical times, and clearly mystery writers have found it so as well. Indeed, there is a whole genre where Jane herself is called upon to smoke out the culprit, while in other books one or more of her characters exposes the guilty. Here, I shall deal only with books without Miss Austen or one of her creations, but I promise to return to these in a future piece once I have read more of the genre. Luckily, they make perfect summer reading!

Looking back over two centuries, we are apt to view the Regency through our finest rose-tinted glasses even though we know that the period was not as charming as we might like to imagine. Not every man was a Mr. Darcy or every lady an Elizabeth Bennet. Nor were most people as rich or polished as we would wish. There was rampant poverty in both town and country and moreover, for most of the period, all of Europe was embroiled in a terrible war both on land and at sea. The death toll was appalling. Even when the war finally came to an end at Waterloo, the years that followed were marked by mass unemployment once the troops returned home to a land that could offer them nothing. To cap it all, in the late teens of the 19th century, the eruption of Mount Tambora in Indonesia caused catastrophic changes to the climate even in far-off Europe. The sun was shrouded in clouds of dust so that crops never ripened. Global famine wreaked havoc.

London was a city of enormous contrasts between the ton and the poor. Try as they might, the place was too crowded for them to avoid each other.

The Miseries of London by Thomas Rowlandson 1807

The period was one of great change, not only politically. Revolutions preceded wars in both the Americas and France. Monarchs lost their heads, most forfeited their kingdoms. The wealthy and the titled lost their money while a new breed rose to the top, one even becoming an emperor.

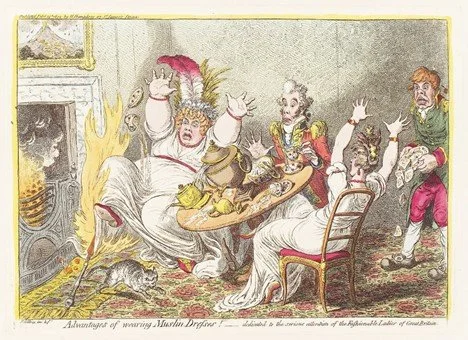

At the start of the period, ladies wore tightly corseted dresses with huge paniers and both sexes wore powdered wigs. But a decade later, the ladies breathed freely in almost diaphanous muslin high-waisted garments that left little to the imagination.

The Advantages of wearing Muslin Dresses by James Gillray 1802

Wigs were abandoned in favour of wearing one’s own hair. Gone was the formal minuet, to be replaced by the lilting waltz, a dance that scandalised those prigs who were more brought up in the stiffer ways of the 18th century.

Waltzing from Life in London by Pierce Egan

In the arts, classical balance and restraint gave way to the beginnings of the wilder romanticism of Lord Byron. In music, the urbanity of Haydn was replaced by the Dionysian creations of Beethoven.

It is no wonder then that this fascinating period should provide inspiration for creative writing almost as soon as the era gave way to the Victorian period. Thackeray’s glorious Vanity Fair is a perfect example, as is Thomas Hardy’s The Trumpet Major, a particular favourite of mine. The first professional detectives were employed in the 1840s and soon after their fictional counterparts began to appear in the works of Edgar Allan Poe and Wilkie Collins. In more modern mysteries set in the Regency, the sleuths are amateurs of both sexes but mostly from the upper end of society.

Before discussing some of my favourite books in this genre, I must confess that I am often rather over pernickety about historical accuracy. Some writers care a great deal about it, but others are less exact. For example, C. J. Sansom whose magnificent series about Matthew Shardlake is set at the end of the reign of Henry VIII, really did consult the annals to see what the weather was like on any particular day. Frank Tallis, whose works are set in Vienna at the time of Freud and Mahler, has an appendix in each book giving chapter and verse for the incidents that occur in them. As I read historical fiction, I wait for a little alarm bell to ring in my head. It makes me think ‘is that date right?’, ‘would a person have used that particular word back then?’ In one that I read recently, a man described himself as an archaeologist which is a term that did not enter the vocabulary until after the Regency. Someone at the time would probably have said that he was an antiquarian. In another, which was set in 1811, a couple visit a hotel for dinner. However, the hotel was not in operation until a decade later. In yet another, set in the same year, waltzes are danced. However, Lord Byron states that the waltz did not arrive until the following year along with whiskers on men and the Pons-Brooks comet. These may seem very trivial, but getting the details right is, I believe, an important part of being a historical novelist.

Quite often, the author will mix historical characters with their fictional ones. There is of course the Regent himself: the louche and slightly grotesque son of George III (whose descent into madness caused the Regency in the first place). His reckless extravagance made him few friends. This print by George Cruikshank brutally shows the Regent frolicking while starvation and death haunt the land outside.

Merry Making on the Regent’s Birthday 1812 by George Cruikshank

Another way to show attention to detail is the use of contemporary language, especially in dialogue spoken by the people in the books. For me, one of the most charming aspects of all Regency mysteries is the use of contemporary slang. Grose’s Pocket Dictionary of the Vulgar Tongue (1811) is a terrific source for how men of all classes actually spoke. Of course, a modern writer can overuse it, sending the poor reader rushing for a dictionary every other line. But I find it delightful to come across unfamiliar words and phrases such as a bufe nabber (a dog stealer), muck, blunt or dung (all meaning money), chatter broth (tea), a mushroom (someone who is nouveau riche), marriage music (the squalling of children) and so forth. The words relating to theft, gambling, sex and those who provide it are almost limitless! The Regency was certainly not an age of prudery!

The first author that I would like to discuss is Kate Ross. Sadly, she only wrote four books before succumbing to cancer in her early forties. Her protagonist is a Regency buck, Julian Kestrel. He is ably assisted by Dipper his valet whose name implies that he had at one time been a pickpocket. High and low life are both there and Ms. Ross has a wonderful talent for recreating the atmosphere of the times not least through her use of Regency slang. Although her first books are set in England, her final work, The Devil in Music, takes Julian Kestrel to Italy. One can only wish that she had been able to live longer and complete more books in her splendid series.

Next, we have C.S. Harris who, like Kate Ross, is American, and who also has the terrific gift for evoking the mood of Regency England. So far, there are twenty books in her series which feature Sebastian St. Cyr, Viscount Devlin. He is from the highest echelon of society but as the books progress, we find that his parentage is by no means certain. His wife is even grander than he, but she has a great interest in the poor and downtrodden of the slums of London, something perhaps rather unusual in one so nobly born. This is a series of books that must be read in order, not only because one can follow the couple through their courtship, marriage and family life but also because the stories are always set against the great events of the Napoleonic War and its aftermath.

Mrs. Harris is such a gifted writer and can conjure the atmosphere of the period with tremendous skill. All her characters are so well-rounded and intriguing from starchy Lord Jervis, the viscount’s father-in-law, to the below-stairs members of his household, not forgetting the rather eccentric surgeon whom the viscount knew in the Peninsular War. The viscount must always have his wits about him as he walks through the rougher and more dangerous parts of London. Indeed, he is mugged and sometimes nearly murdered in almost every book.

Andrea Penrose is my final choice for this preliminary survey of writers. Her main character is an Earl, and he too has a friend who is a surgeon, this time from Scotland. The Earl, rather than just being a gambling dandy, has an interest in science and a taste for danger. His partner in solving crime is a lady artist of great character. Their relationship, at least to begin with, is not especially cordial but as the series progresses….well…..you will have to read further to find out! As in the C.S. Harris books, danger lurks in the dark backstreets just off the fashionable thoroughfares of London.

The fictitious Earl is a member of the Royal Society, where fashionable lecturers such as the very real Humphry Davy frequently spoke. Indeed, many scenes take place there in the first novel. If this interests you, you might also like to check out The Age of Wonder by Richard Holmes, a marvellous book that perfectly captures the spirit of this age where science and discovery were hugely popular in polite society and where the scientists themselves were also poets and composers.

Humphry Davy in Chemical lectures by Thomas Rowlandson.

In a few months, I promise to continue by discussing the mystery stories where Jane Austen is herself the solver of dastardly crimes, and if not her, then one of those magnificent characters she invented and who continue to delight us.

As a teaser, I should mention one of my favourite books in the genre: Death comes to Pemberley. Mr. and Mrs. Darcy are happily married and living in their luxurious Derbyshire country house, but danger hides behind even the most elegant of surroundings. The book is a one-off by one of the queens of detective fiction, P. D. James. Of course, it is beautifully written and, in every way, a cracking good mystery. One can also watch the BBC TV version that was made in 2013 and filmed at Chatsworth, the house that supposedly Jane Austen had in mind as the Pemberley Estate.

Chatsworth. The home of the Dukes of Devonshire, and supposedly the inspiration for Pemberley in Pride and Prejudice.